What this old poem wants you to know about me, evolution, the nature of time and of coalescence - and you

“We shall not cease from exploration” writes T.S. Eliot in his long meditative poem Four Quartets, that reflects on the place of humankind in the constant flow of time. Like an invitation to look back in the turbid history of our Earth’s turbulent cortege of species, he continues:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

A poetic regard on the origin of species

The poem seems to murmur to me: “Where, when did we start?”. And if we all are related, where did I start?

What story can science, this never-ending research, this exploration of ours, tell about me, about you, about us?

If language and culture allow the survival of ideas, concepts and values long after the decay of the body that gave birth to them, when and where will I end?

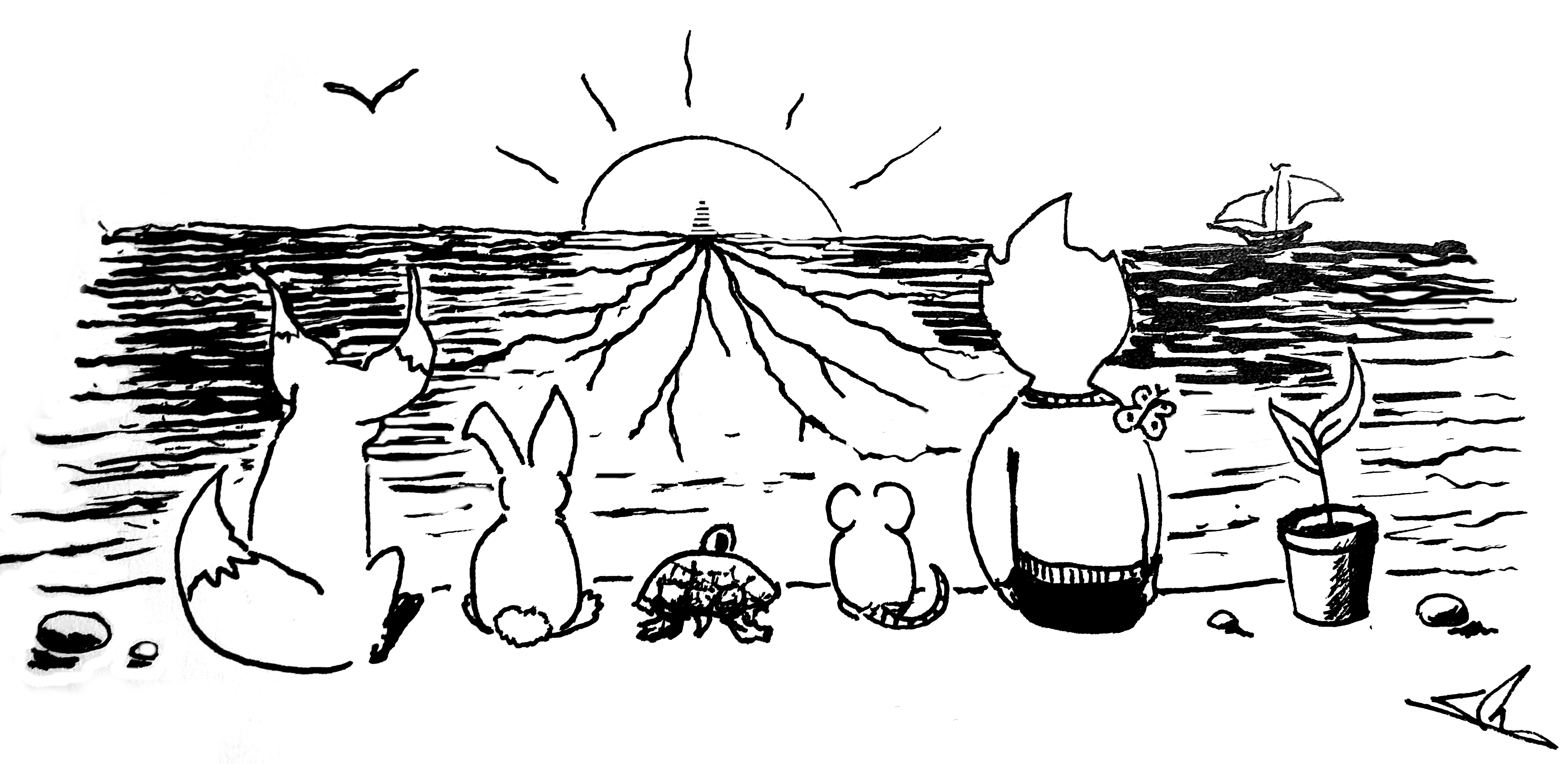

What does it say about those we think as the others: the flying, the swimming, the swarming: when, where, how did they start? What places, what landscapes did they visit along their own journey on Earth?

And beyond our ever-present distinctiveness, do we each remember at least a bit of what we used to be when we were all one and the same “between two waves of the sea”?

Our last universal common ancestor, LUCA, from which all living beings descend, is estimated to have lived not so long after our moon was born, 3 to 4.5 billions years ago, in the deep, dark sea near hydrothermal fissures. These hot waters in contact with magma were rich enough in dissolved minerals to sustain organisms able to use chemical compounds rather than light as a main source of energy.

Diving further in time, the poem continues,

Through the unknown, remembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

At the source of the longest river

The voice of the hidden waterfall

And the children in the apple-tree

Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

My brain responds to this stanza with a multitude of colorful visions: the forever lost landscapes of Vaalbara, the Archean supercontinent at the beginning of time, the future and limits of science, the use and abuse of satellite images, the importance of mystery, its sacredness.

In our modern world where social media shows us places we will never visit and has us listen to people we will never meet, where satellites show us every day every last bit of Earth, and where our most powerful telescopes let us see so far away, so long ago, the poem wonders with me: is there still out-there at least one secret place left undiscovered?

A truly remarkable fact is that we have no concrete fossil, no remaining direct knowledge of LUCA: all that remains today of its evanescent life are blurred but similar patterns shared in the genome of all living creatures. Like a silent voice that genetic studies can hear through all living things: a fleeting echo that still remembers a bit of what it was to be at the source of the longest river: Life.

Hydrothermal remembrance

Primordial words passed down through ages

It is still amazing to me how we can use present information to get a glimpse of a distant past. Because all the livings are related to LUCA, we do share some similarities.

Some can be obvious: most plants are green, while most animals breathe. Some are tricky: a whale has fins, like a salmon, but are warm blooded and produce milk, like us.

Other similitudes, the most spellbinding to me, are invisible to the naked eye: some resemblance in the way our cells work, or in the shape of a protein, or vaguely alike molecular words hidden in the secret of our genetic code.

Since the time our Earth was young, these words have been passed from the first generation down to the next, and to the next, through billions of years, to us, today. They have seen eons, survived cataclysms, have been exposed to untold pressures, have been rewritten countless times, sometimes with a spelling mistake, nothing much, barely a letter changed… But accumulate infinitesimal changes for an infinite amount of time time and …

Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still.

Genetic words are everything but still. Like a tumultuous swarm of young stirlings, they are fluid, chaotic, in constant interactive metamorphosis, always recasted by random mutations that keep altering their initial meaning, pushing us away from other species, further away from LUCA.

But not all changes are welcome: if the genetic alphabet is unable to camouflage the change, if the new word breaks the paramount syntax of its molecular sentence, then it can potentially throw the entire organism into disarray, in a state of molecular dysfunction, and before long, the new words perish with their unfortunate body. Who can imagine the pressure, the burden, the tension that nature and fate exert on these delicate patterns?

This slow decay with imprecision has been used for decades by geneticists, who gave it the name of molecular clock: a ticking, half-hidden voice that counts a tale of its own words, and that with its own unit of time tells us, children of LUCA, how long the road has been since we left our ancestral hydro-thermal shelters. The primal tale of the hidden waterfall, deep beneath the sea.

Looking deep into present genetic data among species has been incredibly useful to understand the past history of Earth’s biodiversity, allowing researchers to predict more accurately how species respond to environmental changes. But not every question has to go back to LUCA.

A people without history still have a tale to tell

Even among members of a same species, the same clock ticks. The more geographically distant two individuals are, the more distant in time their common ancestor was. And, decaying with imprecision, their genetic code begins to slowly diverge, and what made them similar then begins to fade. Tick by tick. Instant mutation by instant mutation. Timeless moment by timeless moment.

A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments.

In a way, subtle diverging tones in my genome and your genome whisper knowledge of how long ago we parted our ways, and of how much time was spent since your ancestors ceased to be my ancestors too.

This is how present genetic patterns can be linked to past ecological processes, answering the oracular question asked in a rigid, reassuring statistical phrasing: “what made them part ways?”.

Was it the emergence of a mountain range that separated us? Was it the overwhelming rising of oceanic waters that transformed our beautiful, unified land into smaller secluded islands? Or was it a freezing wind coming from the North that pushed us to warmer but faraway, isolated refugees?

In what drop of time should the moment be remembered when your ancestor decided to turn West when my ancestor chose East?

Harmonic variations

The children coalescing in the apple tree

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.

This drop of time can actually be vaguely remembered, estimated, through the use of statistical methods.

When a word, a gene, is copied and passed to the next generation, it adds more embranchments to the long genealogy that links us all. This longest river, like any river, can be sailed two ways.

In its natural way, from the past to the present: we then look at organisms being born, growing old, having children to whom they passed a copy of their gene, maybe with some alterations, then die, and so on for thousands, millions of years. Because not everything that lived yesterday still has a descent today, this way shows numerous dead branches: all the organisms that thrived, but whose descendants, somehow, maybe sadly, did not make it.

But we can also look at the flow of life from downstream to upstream: from the still living, isolated bits of DNA that we observe today to their amalgamation into their probable ancestors, their probable habitats, their probable journeys through geological times and geographical spaces, their probable history. This is what geneticists have called coalescence - a poetic name for a statistical way to describe what may have been, starting with the livings. The end is where we start from.

And T.S. Eliot, I could swear, looked upon me through the tree of time when he chose to begin Four Quartets with an epigraph of Heraclitus: The way upward and the way downward is one and the same.

And now I wonder: what did Heraclitus think when he wrote this. Could he imagine that these words would transcend millennia to finally rest in my eyes and find both an echo and a new meaning in my own work, giving to my research on coalescence a more tender, sensitive touch?

The coalescence of two gene copies into a parent copy is simply the replication of the ADN viewed backward in time. The genealogy of the sampled genes copies can be defined backward in time conditionally to a hypothetical demographic process. Coalescence is an important theoretical link between a genetic sample and the historical processes that shaped it, and it can be used for constructing statistical models allowing to estimate properties of these past processes on the basis of the present sample.

The value of patience

My research is all about trying to understand the past history of natural populations: where did the populations begin, where did they go, how did they venture through new territories? How did they overcome the challenges that climate, geology kept throwing at them?

The answers to these questions crystallize so much knowledge: biological intuition, statistical thinking, hard-core computer simulations details coagulated by some software design rules…

To build a strong sense of the past, I need to design a very delicate, fragile, beautiful apparatus.

Sometimes, the apparatus breaks: I look at my mistake, try to understand its nature, gather the broken pieces of my work, mend them back into a new abstract construction, with new shapes, that fit together better this time. Maybe. And I do it again. And again. And again. Often I wonder if I’m doing things right, if I’m somehow good enough to deserve to play with these questions as big as time. The poem somehow foresees the ruminations of my impostor shadow and gently soothes my fears away with six simple words:

Only through time time is conquered.

Welcoming the words into my mind, I breathe and look by the windows, appeased: of course I am enough. You are enough. We all are, always were, and always will be enough.

Things just take time, and time conquers all.

Foreword

Did T.S. Eliot think about all of this when he wrote Four Quartets?

Probably not

But I don’t think there is a point in knowing exactly what he thought when he was laying these words on paper for posterity. Would he have wanted us to know, he would have told us in a clear form, closed to interpretation. And it would not have been a poem, and its words would not have reached posterity: who cares for the exact details of the inner life of a long dead man?

Poetry, to me, is the art to tell and teach different things to different readers, or to the same reader at a different time of their life. Poems are not static statements of eternal and objective knowledge: they are fluid, ever-changing, always conjuring another word, another memory, with a slightly altered meaning, never walking twice the same path in the maze of our feelings and emotions.

That’s what makes them so powerful.

Maybe a bit like abstract theorems can be used on surprising new and unforeseen grounds, the metaphoric, volatile, associative nature of words allows poems to mirror different questions at different times in History, offering different answers to everyone of us. In a way, and maybe like a good friend or a good therapist, they just echo a truth we already know.

But among the divergent, infinite interpretations of their same text, the poet knows how to have us look for a unifying truth: the secret meaning of the poem they want us to discover. And I have the feeling I barely touched it.

Relatedness, between two waves of the sea