Singleton - An Anti-Pattern in Disguise?

Only if you abuse this pattern

I once joined a medical device project where the codebase was riddled with Singletons. The code was legacy, inherited from years of development, and completely untested. When I tried to understand and improve the system, I discovered that multiple Singletons interacted throughout the codebase. Classes with seemingly simple interfaces were hiding calls to five or six different global Singletons in their implementation files.

Testing was impossible. Every attempt to isolate a component for testing dragged along the entire system. I battled concurrency timing issues that were nearly impossible to debug. The Singletons had locked the entire codebase together into one monolithic, fragile mass.

My colleagues asked me to share what I’d learned about why this happened and how to avoid it. This article grew from that knowledge-sharing presentation. The experience was painful. I had known since my PhD that I should stay away from Singletons’ false promises, but I had never witnessed how much damage it could do to a project. That’s what motivated this article. Let’s dissect this cancerous design choice.

What is the Singleton Pattern?

The Singleton pattern ensures a class has only one instance during the program lifecycle and gives you global access to it. The class controls its own creation through a private constructor and a static method.

Here’s what it looks like in C++:

class DatabaseConnection {

private:

DatabaseConnection() { /* initialize */ }

public:

static DatabaseConnection& instance() {

static DatabaseConnection instance;

return instance;

}

// Delete copy and move operations

DatabaseConnection(const DatabaseConnection&) = delete;

DatabaseConnection& operator=(const DatabaseConnection&) = delete;

};

// Usage

DatabaseConnection::instance().query("SELECT * FROM users");

One important detail: only the instance creation is thread-safe since C++11. Multiple threads can call instance() at the same time without problems. But accessing the member data? That still needs synchronization.

Why Singleton Becomes an Anti-Pattern

A Global Variable in Disguise

The Singleton looks clean and encapsulated. But really? It’s just a global variable with extra steps. Look at this:

class UserService {

public:

void createUser(const std::string& name) {

// Direct dependency on concrete Singleton

DatabaseConnection::instance().insert(name);

}

};

The UserService class has a hidden dependency. Look at its interface - nothing tells you it needs a DatabaseConnection. You have to dig into the implementation to find out. This breaks the Dependency Inversion Principle because you depend on a concrete class, not an abstraction. It also breaks Single Responsibility because now the class handles user creation AND finding the global database.

Hidden dependencies make your code harder to understand, test, and change. You can’t see what a class really needs just by looking at it.

Tight Coupling to Concrete Implementations

The Singleton pattern locks your code to one specific implementation. Here’s what happens when you need to change things:

class OrderProcessor {

public:

void processOrder(int orderId) {

DatabaseConnection::instance().update(orderId);

}

};

Suppose you need to support multiple database types because the client says so, or switch to a test database during development, or use a mock database for unit tests. With the Singleton approach, you’re stuck. The OrderProcessor is hardcoded to use DatabaseConnection, and there’s no way to substitute a different implementation without modifying the source code. Don’t be fooled by the apparent simplicity of this code snippet: in a real codebase, this change can be extremely expensive.

This breaks the Open/Closed Principle. Your classes should be open for extension but closed for modification. Need to change the database? With Singletons, you have to modify every class that uses it.

You Can’t Substitute It

The tight coupling creates another problem: you can’t swap the Singleton for something else. There’s no abstraction to swap in the first place. This breaks the Liskov Substitution Principle.

Testing becomes painful. How do you test that OrderProcessor works without a real database? With Singletons, you can’t. No mocks, no stubs. Every test uses the real thing. Tests become slow, fragile, and dependent on each other.

And it’s not just testing. You can’t have different configurations for development, staging, and production. You can’t experiment with different implementations. You can’t optimize for specific cases. The Singleton locks you in.

Why Testing Becomes a Nightmare

Testing shows just how much damage Singletons can do.

You Can’t Mock Dependencies

Consider testing a service that uses a Singleton database connection:

// How do you test this without a real database?

TEST(UserServiceTest, CreateUser) {

UserService service;

service.createUser("Alice");

// DatabaseConnection::instance() is the REAL database!

// Cannot inject a mock

}

Without mocks, your unit tests need a real database. This makes tests slow (database operations are way slower than in-memory), fragile (network problems, database down, config issues all break tests), and expensive (you need database infrastructure just for testing).

Unit testing means testing one unit alone. Singletons make that impossible.

Tests Pollute Each Other

Tests sharing a Singleton instance pollute each other’s state:

TEST(Test1, ModifiesDatabase) {

DatabaseConnection::instance().insert("test data");

// State persists in the Singleton...

}

TEST(Test2, ExpectsCleanState) {

// But the database still has data from Test1!

// Tests are now ORDER-DEPENDENT

}

Test frameworks run tests in random order or in parallel to catch hidden dependencies. With Singletons, this doesn’t work. Tests need a specific order. Each test must clean up carefully. One mistake breaks your entire test suite.

Gets worse with more tests. Tracking down why a test only fails after running another specific test? That’s a special kind of hell. Singletons turn your test suite from a safety net into a source of random failures.

Concurrency Problems

Modern C++ makes Singleton creation thread-safe. But that’s only half the story. The real problems come when multiple threads use the Singleton’s data.

Here’s a cache as a Singleton:

class Cache {

private:

std::map<std::string, std::string> data;

Cache() = default;

public:

static Cache& instance() {

static Cache cache;

return cache;

}

void set(const std::string& key, const std::string& value) {

data[key] = value; // NOT THREAD-SAFE!

}

};

The instance() method is thread-safe - C++11 guarantees static local variables get initialized exactly once, even with multiple threads. But the set() method? It modifies data, which all threads share. Without synchronization, concurrent set() calls can corrupt the map. Crashes, undefined behavior, the usual fun stuff.

You might add a mutex. Sure, that prevents corruption. But now you have a global bottleneck. Every thread waits for the mutex. Parallel operations become sequential. As you scale to more threads, this becomes a real problem.

Gets worse with multiple Singletons. A logger Singleton uses a config Singleton, which uses a filesystem Singleton. Now you have multiple locks to acquire in the right order to avoid deadlocks. Good luck reasoning about lock order across your whole application.

And testing? How do you write deterministic tests for thread-safety when the Singleton persists across runs? How do you simulate race conditions reliably? The global shared state makes multi-threaded testing extremely hard.

Lessons from the Trenches

Let me tell you more about that medical device project. I’ll transform the problems a bit for confidentiality. The system had Singletons everywhere: device communication, configuration, logging, data storage. Each one looked reasonable when you looked at it alone. But together? A complete mess.

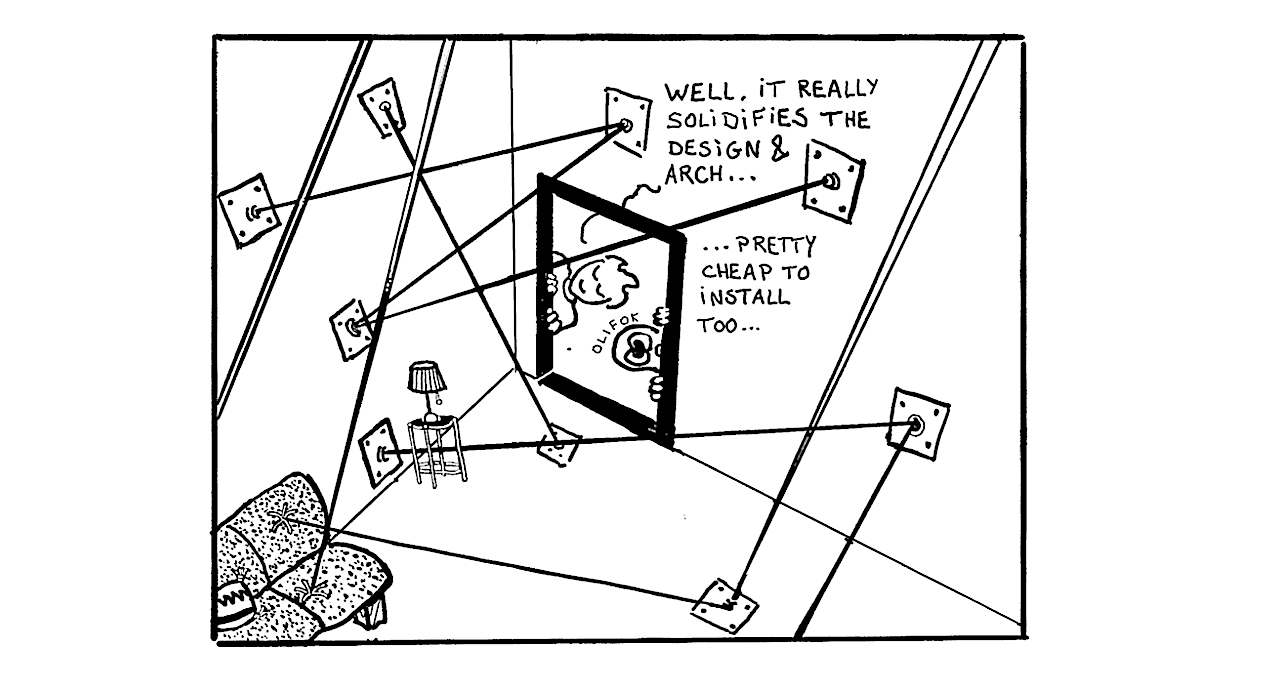

What really frustrated me was the deceptive simplicity. You’d see a class with a constructor taking no parameters, a few simple methods. Looks clean, right? Wrong. You had to dig into the implementation to discover the Singleton calls hidden inside. The interface was lying about what the class really needed.

Try to instantiate a simple data processing class? Boom. It triggers the device communication Singleton, which expects actual hardware. The Singletons locked data processing with data generation and the UI into one giant block. You couldn’t test anything in isolation. To test one small component, you had to mock or disable five or six different Singletons scattered through the code. And the threads? They were accessing different Singletons in random orders. The UI was behaving erratically. The interaction matrix was impossible to understand.

Here’s something interesting for the AI era: when you ask an AI to help with code that has hidden Singleton dependencies, it has the same problem we have. It can’t guess from the interface that Singletons are called inside. It has to read the entire implementation, follow calls through multiple files, which makes the context window explode. A simple question about one class interface turns into investigating ten interconnected files. If the code is hard for us to understand, it’s equally hard for AI tools.

A Common Mistake

This mess comes from an actually simple misconception. Many developers use the Singleton pattern based on this wrong idea:

“My application has only ONE database, so my code must have ONE instance.”

This mixes two different things: what you have in your deployment versus how you write your code. Just because there’s one database server doesn’t mean your code needs a global Singleton object.

Think about it. Your application has one internet connection, but you don’t create InternetConnection::instance() everywhere. You pass network objects where needed. Same thing applies to databases, configuration, logging, and other resources that happen to be unique in your deployment.

The number of resources you have is a deployment detail, not an architectural constraint. Your code should work the same whether there’s one database or ten, one configuration file or several. The Singleton pattern forces deployment details into your architecture. That makes code rigid and hard to test.

Better Alternatives

Dependency Injection

Pass dependencies through constructors. Instead of grabbing a global Singleton, classes receive what they need from outside.

Many developers reach for runtime polymorphism (virtual functions and inheritance) by reflex. But virtual calls have overhead. Here’s another approach using concepts - the compiler checks your types and gives clear errors, everything gets inlined, zero runtime cost. Sometimes you do need virtual functions (storing different types in containers, plugin systems), but for most dependency injection? You don’t. This is also a matter of personal taste - I’m still exploring what works best in different contexts.

#include <concepts>

// Define what a database connection must do

template<typename T>

concept DatabaseLike = requires(T db, const std::string& data) {

{ db.insert(data) } -> std::same_as<void>;

{ db.query(data) } -> std::same_as<void>;

};

// Implementations (no inheritance needed)

class DatabaseConnection {

public:

void insert(const std::string& data) { /* real work */ }

void query(const std::string& sql) { /* real work */ }

};

class MockDatabaseConnection {

public:

void insert(const std::string& data) { /* record call */ }

void query(const std::string& sql) { /* return test data */ }

};

// Service uses the concept

template<DatabaseLike DB>

class UserService {

private:

DB& db;

public:

explicit UserService(DB& database) : db(database) {}

void createUser(const std::string& name) {

db.insert(name);

}

};

// Production usage

DatabaseConnection realDb;

UserService service(realDb); // Type deduced!

// Testing

MockDatabaseConnection mockDb;

UserService testService(mockDb); // Type deduced!

Dependencies are explicit and visible. Testing is easy. You can swap implementations. All without Singletons.

Scope and Lifetime Management

For complex scenarios, use a container object to manage dependency lifetimes:

class Application {

private:

DatabaseConnection db;

Cache cache;

Logger logger;

public:

Application()

: db(loadConfig("db")),

cache(loadConfig("cache")),

logger(loadConfig("logger")) {}

UserService createUserService() {

return UserService(db, logger);

}

OrderProcessor createOrderProcessor() {

return OrderProcessor(db, cache, logger);

}

};

The Application class is your composition root. It creates and manages shared dependencies. Services get their dependencies through injection, but Application makes sure expensive resources like database connections are created once and reused.

You get the benefits of shared instances (efficiency, consistent config) without global state. Each service has clear, testable dependencies. You can easily create different Application setups for testing, development, and production.

Factory and Registry Patterns

Need centralized creation but want to avoid global state? Factories and registries are a middle ground:

class ServiceRegistry {

private:

std::map<std::string, std::shared_ptr<IService>> services;

public:

void registerService(const std::string& name,

std::shared_ptr<IService> service) {

services[name] = service;

}

std::shared_ptr<IService> getService(const std::string& name) {

return services.at(name);

}

};

// Usage

ServiceRegistry registry;

registry.registerService("database", std::make_shared<DatabaseService>());

registry.registerService("cache", std::make_shared<CacheService>());

// Components receive the registry via dependency injection

class Application {

private:

ServiceRegistry& registry;

public:

explicit Application(ServiceRegistry& reg) : registry(reg) {}

void run() {

auto db = registry.getService("database");

// Use the database...

}

};

The registry itself gets passed through dependency injection, not accessed globally. You keep centralized service management but preserve testability and flexibility.

When Can You Use Singleton?

After all these problems, you might wonder if Singleton is ever okay. Answer: rarely, and carefully.

The pattern might work when you have a truly unique resource that’s fundamentally global, and where the benefits clearly beat the testing and maintenance costs. But even then, ask yourself if dependency injection would work just as well.

Possible cases: logging systems (though I’d rather pass a logger reference), hardware interfaces to truly unique devices (though I’d consider abstracting the interface), or performance-critical caches where alternatives are too expensive.

But think about the tradeoffs. Is the small performance gain worth harder testing? Could you use dependency injection with a single instance at the application level? Would swapping implementations for testing or different environments be valuable?

Most of the time, what looks like a good Singleton fit can be solved better with dependency injection and proper lifetime management. Singleton is seductive because it’s simple. But that simplicity costs you long-term maintainability.

Conclusion

The Singleton pattern looks simple and elegant. But it creates problems that get worse over time. What starts as convenient access to a shared resource becomes a mess of hidden dependencies, unmockable code, and global state.

The pattern stays popular because it’s easy. A few lines of code give you global access to anything. But this convenience is a trap. The costs show up later - when you need to test, when you want to reuse components in different contexts, when you need to change the implementation without breaking everything.

In most cases, dependency injection with proper lifetime management is better. It makes dependencies explicit, enables testing with mocks, respects SOLID principles, and produces code that’s easier to understand, change, and maintain.

Key Problems with Singleton

- Hides dependencies behind global state, violating Dependency Inversion and Single Responsibility Principles

- Creates tight coupling to concrete implementations, making code rigid and violating the Open/Closed Principle

- Makes testing difficult due to unmockable dependencies and shared global state

- Multiplies concurrency problems as global shared state creates bottlenecks and deadlock risks

- Confuses deployment with architecture - a single resource doesn’t mean you need a single instance in code

Better Approaches

- Dependency injection: pass dependencies explicitly through constructors

- Lifetime management: let a composition root manage object lifetimes

- Factory and registry patterns: centralize creation logic without global state

- Question yourself: before using Singleton, carefully assess if convenience justifies the maintenance cost

Don’t use patterns blindly. They come with trade-offs. If you can’t give a clear and complete explanation of why you want to use a tool, it means you don’t understand it (yet). And it will not be long before this misunderstanding will translate into untestable code, then random bugs, then missed deadlines, then frustrated teams and ultimately unhappy clients.