Policy-Based Design versus Combinatorial Hell

Dependency injection that doesn't lock you in

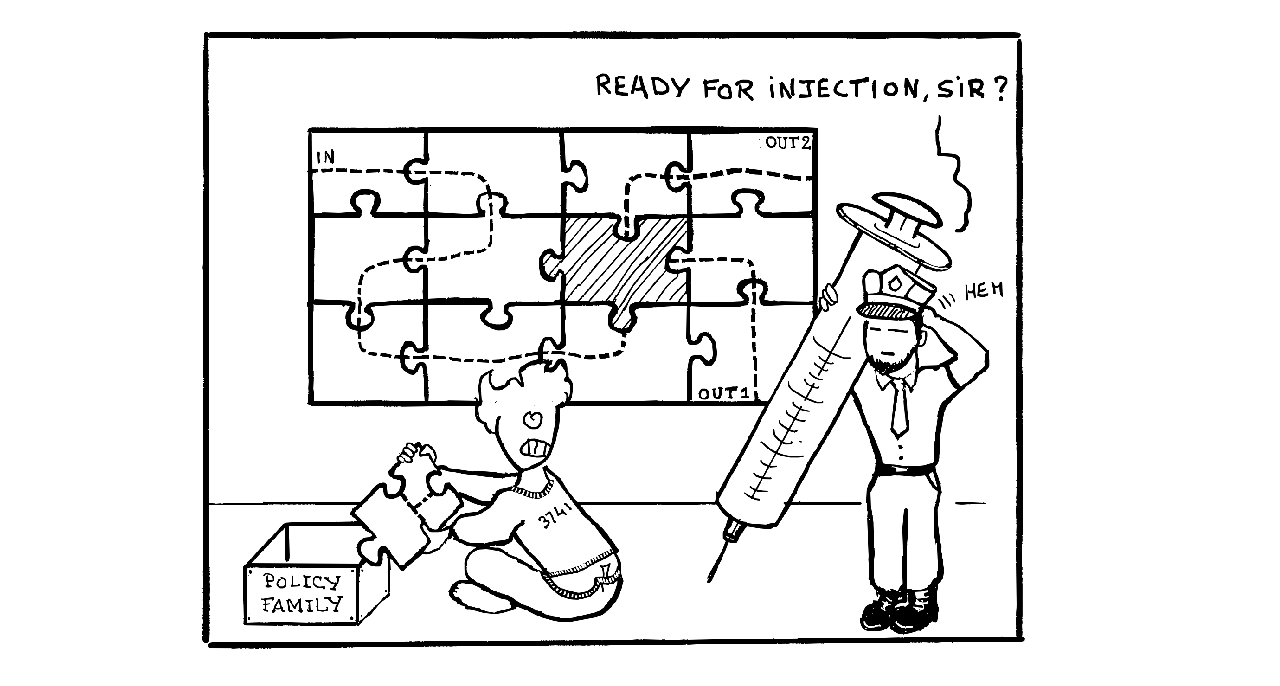

You know the feeling: you start with a simple class, then someone asks “can we support an alternative strategy for X?”, so you add a parameter. Then “what about different approaches to Y?”. Okay, another parameter. “And different handlers for Z?”. And so on…

For example, consider a data processing pipeline where to have to tackle different input formats (JSON, XML, CSV), several data validation strategies (strict, lenient, custom), alternative output destinations (file, database, network), different error handling approaches (throw, log, ignore). That’s already 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 = 81 combinations. Add caching strategies? Now you’re at 243. And compression options? 729.

Before you know it, your innocent little class has morphed into a monster with 720 possible combinations of behaviors to test and maintain. Welcome to combinatorial hell. If you are a reasonable engineer, you will ask yourself: how to get the flexibility without the madness?

No-Go approach

Let’s say you’re building a logging system. You need to support three different formatters (plain text, JSON, XML), two output destinations (console, file), and two threading models (synchronous, asynchronous).

The “just use a function” trap

How many times did I hear managers, juniors, coworkers alike say things like “Easy, just make one class with parameters”:

class Logger {

Format format_;

Destination dest_;

Threading threading_;

public:

Logger(Format format, Destination dest, Threading threading)

: format_(format), dest_(dest), threading_(threading) {}

void log(const std::string& message);

};

Neat. What they don’t see is that you still need to implement all the logic for every combination. Inside that method, you’ll end up with nested switches or if-statements:

void Logger::log(const std::string& message) {

std::string formatted;

// First switch for formatting

switch(format_) {

case Format::PlainText: formatted = format_plain(message); break;

case Format::JSON: formatted = format_json(message); break;

case Format::XML: formatted = format_xml(message); break;

}

// Second switch for destination

switch(dest_) {

case Destination::Console:

// Third switch for threading

switch(threading_) {

case Threading::Sync: write_console_sync(formatted); break;

case Threading::Async: write_console_async(formatted); break;

}

break;

case Destination::File:

switch(threading_) {

case Threading::Sync: write_file_sync(formatted); break;

case Threading::Async: write_file_async(formatted); break;

}

break;

}

}

Look at all the nested logic: the combinatorial explosion just moved inside your function. You’re still writing and testing all 12 combinations. Plus you get runtime overhead for all those branches. I kept it simple for the blog, but the beauty of combinatorial explosion is that it rarely stays at 12. It wants to grow exponentially, unlike your maintenance linear capability or fast-decaying patience curve.

The explicit class-per-combination approach

An even more naive approach would be to create a separate class for each combination:

class PlainText_Console_Synchronous { /*...*/ };

class PlainText_Console_Asynchronous { /*...*/ };

class PlainText_File_Synchronous { /*...*/ };

// ... 12 total classes for just 3 simple dimensions

Silverlining myself, I would try to convince myself that at least the nested switches are gone. But now we have massive code duplication. That’s 12 classes already. Add one more dimension and you’re at 24. Add another and the explosion continues. And you have to refactor the class name every time you add a dimension. Not great, admittedly.

Both approaches suffer from the same fundamental problem: the dimensions are not decoupled, so you’re paying a hefty price for every combination, whether in branching logic or in duplicated code. You need to extract each behavior into fully independent components, so you can compose them. This is orthogonality, a key design principle.

The orthogonality principle

Remember linear algebra. With only orthogonal vectors in 3D space, any point can be expressed as a linear combination of those three vectors. You don’t need to define every possible point explicitly: you just need to combine the base vectors:

$\vec{P} = a\vec{u} + b\vec{v} + c\vec{w}$

The key insight is: three orthogonal vectors give you access to infinite points in 3D space through composition, not enumeration. Software design works the same way, as each behavioral dimension should be:

- Independent: Changing the formatter shouldn’t require touching the output destination code

- Composable: Any formatter should work with any destination with any threading model

- Complete: Each component fully handles its own responsibility

When dimensions are truly orthogonal:

- 3 formatters × 2 destinations × 2 threading models = 12 combinations

- But you only write: 3 + 2 + 2 = 7 independent components

Compare this to the nested switch approach that explicitely handled all combinations, or the class-per-combination nightmare with massive duplication. As we add dimensions, orthogonal design scales linearly (n components) but coupled design scales exponentially. It’s a pretty big deal for maintenance, documentation and testing.

For example, if you were to add caching strategies with 3 options:

- Orthogonal Design has you write 1 new component (total: 8 components for 36 combinations)

- Coupled Design has you write 24 new switch branches or classes (total: 36 implementations)

That’s the power of orthogonality: you escape combinatorial hell by making your dimensions truly independent. It’s a good, SOLID Ariadne’s thread to follow. But there are so many ways to extract, apply and compose components. How to chose?

Quick and Dirty approach: enums and switch

You could simply pass options (as strings or, better, enums) to a class constructor that wraps a switch statement:

enum class Format {PlainText, JSON, XML};

class Logger {

Format format_;

public:

Logger(Format format) : format_(format) {}

void log(const std::string& message) {

switch(format_) {

case Format::PlainText:

std::cout << message << std::endl;

break;

case Format::JSON:

std::cout << "{\"message\": \"" << message << "\"}" << std::endl;

break;

case Format::XML:

std::cout << "<message>" << message << "</message>" << std::endl;

break;

}

}

};

// Usage

Logger json_logger(Format::JSON);

json_logger.log("Hello");

This can work, but it comes with drawbacks:

- Adding a variant requires updating both the enum and the switch (possibly in different files), increasing merge conflict risks

- All branches must return the same or convertible type, locking in the signature. This matters because JSONObject can have methods for manipulation that strings lack.

- Client code cannot inject external behaviors unknown to your library

- The dispatch happens at runtime even when the choice is known at compile time

Choose this approach when:

- The variant set is small (3-5 options) and stable

- You can accept the runtime overhead

- Variants are the library’s internal responsibility

If these trade-offs work for you, then it’s a reasonable starting point.

A compile-time variant

Assuming C++17 is available to you, a slight design variation could be to use if constexpr:

enum class Format {PlainText, JSON, XML};

template<Format F>

class Logger {

public:

void log(const std::string& message) {

if constexpr (F == Format::PlainText) {

std::cout << message << std::endl;

} else if constexpr (F == Format::JSON) {

JSONObject objmessage;

std::cout << obj.serialize() << std::endl;

} else if constexpr (F == Format::XML) {

std::cout << "<message>" << message << "</message>" << std::endl;

}

}

};

// Usage: each Logger type is specialized at compile-time

Logger<Format::PlainText> plain_logger;

plain_logger.log("Hello"); // std::string handling

Logger<Format::JSON> json_logger;

json_logger.log("Hello"); // JSONObject handling

This approach solves two of the previous drawbacks:

- The dispatch happens at compile time, not runtime

- Each branch can return a different type (no need to flatten everything to strings)

However, adding new formats still requires modifying both the enum and the function body. You can’t extend this from outside your library, and you still need to touch multiple points in the code for each new variant. The Open-Closed Principle violation remains: the code is not closed for modification.

Both the runtime switch and if constexpr approaches share a fundamental limitation: they’re still enum-based. The variants are baked into an enum, and the logic is centralized in one function. What if we could decouple the variants entirely? What if each formatter was its own independent type, composable at compile-time? This would give us true extensibility (clients can add formatters without touching your code), preserve the compile-time optimization, and eliminate the need for centralized switch logic.

Enter Policy-Based Design

Policy-based design solves this by turning behaviors into independent types rather than enum values. Each behavior becomes a self-contained class. Users can provide their own types without modifying your library. The host class takes template parameters and composes them. The compiler generates a specialized version for each combination you actually use—zero runtime overhead, full extensibility.

Why use a class to host policies rather than template functions? Classes own policy state (file handles, buffers, configuration), compose multiple policies together, and support RAII for resource cleanup. Template functions would require passing policy instances on every call, losing these benefits.

The actual cost of such decoupling is obviously less cohesion: it can be harder to find the relationship between a policy class and its host class. Concepts in C++20 help a bit to tighten them together.

You’ve been using policy-based design without realizing it. STL containers take allocators for custom memory management, std::basic_string takes std::char_traits (that’s how you’d implement case-insensitive strings), std::map takes custom comparison functions, and std::unordered_map takes custom hash functions and equality predicates. The standard library proves the design works in a user-friendly way.

Let’s revisit our logging system with a policy-based approach:

// The host class takes the formatter as a template parameter

template<typename FormatterPolicy>

class Logger {

FormatterPolicy formatter_;

public:

void log(const std::string& message) {

auto formatted = formatter_.format(message);

std::cout << formatted << std::endl;

}

};

// Each formatter is now an independent class

struct PlainTextFormatter {

std::string format(const std::string& msg) {

return msg;

}

};

struct JSONFormatter {

JSONObject format(const std::string& msg) { // Different return type!

return JSONObjectmessage;

}

};

struct XMLFormatter {

std::string format(const std::string& msg) {

return "<message>" + msg + "</message>";

}

};

// Usage: pick your formatter at compile-time

Logger<PlainTextFormatter> plain_logger;

plain_logger.log("Hello"); // Output: Hello

Logger<JSONFormatter> json_logger;

json_logger.log("Hello"); // Output: {"message": "Hello"}

No more enums, no centralized switch. Each formatter is self-contained. Want to add a new formatter? Just define a new class: no need to touch Logger or modify any enum. Users can even provide their own formatters from outside your library.

How to compose policies

The real power emerges when you compose multiple orthogonal policies. Observe how we can extend our logger with separate formatting and output policies:

// The host class now takes TWO independent policies

template<typename FormatterPolicy, typename OutputPolicy>

class Logger {

FormatterPolicy formatter_;

OutputPolicy output_;

public:

void log(const std::string& message) {

auto formatted = formatter_.format(message);

output_.write(formatted);

}

};

// Output policies - completely independent from formatters

struct ConsoleOutput {

void write(const std::string& msg) {

std::cout << msg << std::endl;

}

};

struct FileOutput {

std::ofstream file_;

FileOutput(const std::string& path) : file_(path) {}

void write(const std::string& msg) {

file_ << msg << std::endl;

}

};

struct NoOpOutput {

void write(const std::string&) { /* do nothing */ }

};

// Usage: any formatter works with any output!

Logger<PlainTextFormatter, ConsoleOutput> console_logger;

Logger<JSONFormatter, FileOutput> json_file_logger("log.json");

Logger<XMLFormatter, NoOpOutput> silent_logger; // Useful for testing

Notice the orthogonality: we have 3 formatters and 3 outputs, giving us 9 possible combinations by writing only 6 independent classes. Add a third policy dimension (threading, buffering, filtering) and the composition scales linearly while your flexibility grows exponentially.

When NOT to use policy-based design

Like any powerful tool, policy-based design has its place. Don’t use it when:

- The policies are large and complex: If a “policy” is several thousand lines of code, it’s probably not a policy

- You need runtime configuration: If users choose behavior at runtime based on config files or user input, runtime polymorphism is more appropriate. Beware: you can almost always mistakenly think a compile-time choice is a runtime one. Be aware of the difference.

- You’re sharing interfaces across DLL boundaries: Template classes can’t cross DLL boundaries easily

- Code bloat is a concern: Each policy combination generates a separate template instantiation in your binary. For example,

Logger<JSON, File>andLogger<XML, File>create two complete class definitions. If you instantiate many combinations, binary size can balloon. This is why C++17 introducedstd::pmr::polymorphic_allocatorandstd::pmr::memory_resource: they use runtime polymorphism (virtual functions) to avoid generating dozens ofstd::vectorinstantiations for different allocators, trading some performance for smaller binaries. - Compilation time is already problematic: Template-heavy code can slow down compilation.

Why not just use OOP?

You might be thinking: “Inheritance and virtual functions solve this too, right?”

class Logger {

std::unique_ptr<Formatter> formatter;

void log(const std::string& message) {

formatter->format(message); // virtual call

}

};

Runtime polymorphism works great when you genuinely need runtime flexibility—like a plugin system where third-party DLLs get loaded at startup. It’s also the right choice when code bloat becomes a problem. The standard library itself demonstrates this trade-off: C++17 introduced std::pmr::polymorphic_allocator and std::pmr::memory_resource specifically to avoid generating dozens of std::vector instantiations for every allocator combination. They use virtual functions to trade a bit of performance for significantly smaller binaries.

But if your behavior choices are known at compile-time and binary size isn’t an issue, policy-based design avoids unnecessary costs:

Performance overhead: Virtual calls prevent inlining and block compiler optimizations. In high-throughput systems (web servers, message queues), this can be the difference between 10,000 and 50,000 requests per second.

Type information loss: With virtual functions, all formatters must return the same type. Your JSONFormatter can’t return a rich JSONObject: it’s forced to flatten everything to strings to match the base class interface.

The key is choosing the right tool: policies when you know the strategy at compile-time and performance matters, OOP when you need runtime flexibility or want to control binary size.

Conclusion: freedom without fear

Policy-Based Design offers an important capability in software engineering: the ability to be flexible without paying for it. Also, keep in mind policies are unitary testable, and very mobile: I pasted them along with their tests across several projects. The atomicity of a policy compared to the complexity of an entire enum based switch is a blessing for reusability.

Whether you’re building data processing pipelines, game engines, or embedded systems, you often need to explore different strategies, test different approaches, and combine behaviors in novel ways. This flexibility is essential. But your code also needs to be fast. You can’t afford to pay for flexibility you don’t use.

Policy-Based Design is a way to get both.

The compiler is your friend. Give it the information it needs (via templates) and it will generate efficient code for you. Fight the compiler (by hiding information behind runtime indirection) and you both suffer.

So next time you’re facing a combinatorial explosion of behaviors, don’t reach for inheritance and virtual functions. Don’t resign yourself to copy-pasting code. Reach for policies, let the compiler do the heavy lifting, and get back to solving your actual problem.

Real-world example: Boost.Bloom

Boost.Bloom, authored by Joaquín M López Muñoz, implements Bloom filters: space-efficient probabilistic data structures analogous to compressed databases, useful for fast membership testing. Full disclosure: I served as Review Manager when this library was accepted into Boost.

Bloom filters work by hashing elements and setting specific bits in an array. The hash function determines which bits get marked, and its quality affects the filter’s accuracy. A poor hash function causes collisions and false positives and a good one distributes bits uniformly. But users might bring domain-specific hashes, legacy code hashes, standard library hashes of varying quality, so the library can’t force one “good-enough” implementation on everybody.

The domain problem: Hash functions vary wildly in quality: high-quality ones produce well-distributed values that work great as-is, but poor-quality ones need additional bit mixing to avoid collisions.

The user’s need: Users with good hash functions shouldn’t pay for mixing they don’t need. Users with poor hash functions should get automatic enhancement. Checking hash quality at runtime would add overhead to every operation.

The developer’s solution: A policy family that the compiler selects based on hash traits:

struct no_mix_policy {

static uint64_t mix(const Hash& h, const T& x) {

return (uint64_t)h(x);

}

};

struct mulx64_mix_policy {

static uint64_t mix(const Hash& h, const T& x) {

return mulx64((uint64_t)h(x)); // Applies bit mixing

}

};

The library selects the appropriate policy at compile time based on hash function traits:

using mix_policy = typename std::conditional<

unordered::hash_is_avalanching<Hash>::value, // Avalanching (small input changes → large output changes) ensures uniform bit distribution

no_mix_policy, // Good hash: no mixing needed

mulx64_mix_policy // Poor hash: apply mixing

>::type;

The result: Users with good hash functions pay zero cost. Users with poor hash functions get automatic enhancement. No runtime checks, no virtual calls, no wasted cycles. The right strategy for your situation, decided at compile time.

Want to see more? Check out Andrei Alexandrescu’s “Modern C++ Design” for the definitive treatment of policy-based design. Or explore Boost.Bloom to see policies in action, and my Quetzal library to see these ideas applied in a different domain.